Healthcare insurance is an important topic for me personally. I grew up in West Virginia where my father was a coal miner. For most of my youth, he was unemployed due to downturns in the coal industry and, more often than not, we were supported by Federal and State welfare programs. We didn’t have medical insurance most years so I know how it feels to be constantly concerned about illness and injury and whether we could pay for medical bills. As a result, I still struggle with white coat syndrome to this day. Needless to say, I’m very supportive of the effort to make good affordable healthcare available to everyone who wants it.

The continuing debate on whether to repeal and replace or to implement improvements to the Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) is hard to avoid. While I do have a personal view of the benefits and drawbacks of Obamacare, I’ve become most concerned about the impacts on small businesses and their employees. Small businesses are often lost in this debate that most often focuses purely on the poor and unemployed. This is unfortunate as small business owners, their employees and their dependents have always been and continue to be a substantial portion of the uninsured in the US.

A Few Facts to Warm-Up Our Thinking About the Importance of Small Businesses

In the US, small businesses deliver about half of the private nonfarm GDP (see SBA) and in 2016 accounted for 99.5% of all private sector firms and 53.2% of private sector employees. Small businesses are typically defined as firms with 1 to 499 employees. I find this definition of small business to be quite broad and prefer to use the term as meaning firms with less than 100 employees. In my view, firms with several hundred employees operate quite differently than those with fewer than 100 employees and have a significantly altered set of business risks to manage. Small businesses by this definition accounted for 97.5% of firms in 2016 and 35.8% of all employees. Further “mini-businesses” (firms with 1 to 50 employees) accounted for 94.9% of all firms and 28.0% of all employees, while “micro-businesses” (firms with 1 to 9 employees) accounted for 55.6% of all firms and 10.3% of all employees. {Notes: 1) total firms of 5,134,000 excludes non-employer firms; 2) total private sector employees were 118,042,000; and 3) see here for Bureau of Labor Statistics on firm size and employment change data.}

It shouldn’t be a stretch then to conclude that small businesses are a very important part of our economy and our sources of employment. In addition to being sizable, small businesses have a major impact on job creation. Between 1992 and 2016, small businesses with less than 100 employees accounted for 49.1% of net jobs created in the US with mini-businesses accounting for 32.2% of that total and micro-businesses accounting for 11.9%. If job growth in our economy is important to you, then supporting small businesses should be a clear priority.

And just so you don’t lose your economic connection to this group, the median income for individuals who were self-employed at their own incorporated businesses was $49,204 in 2014.

The State of Healthcare in Small Businesses prior to Obamacare

Of the 45.7 million people (15.3% of population) without health insurance in 2007, uninsured workers aged 18 to 64 years comprised 26.8 million of that total (58.6% of total uninsured). Of these uninsured workers, nearly 63% were self-employed small business owners and their employees (<100 employees). Thus, this group of uninsured small business owners and employees accounted for about 37% of the total uninsured in 2007. If you add in the dependents of this group as well, the estimate for the percentage of total uninsured in 2007 accounted for by small business owners, their employees and their dependents climbs to 57%. That’s a big number and was a big part of the issue back in 2007.

There are good reasons why small businesses couldn’t afford to pay for healthcare. For instance, from 1999 to 2007, family health insurance premiums for employees of small firms (3 to 199 employees) increased 108%. Not surprisingly, worker contributions during this same period increased 131% as employers passed a large portion of the increases along to the employees. Add to this the fact that small firms typically paid 18% more for comparable health insurance than larger firms and you can see that small businesses and their employees were in a challenging environment. See here for Kaiser Family Foundation statistics.

Small Business Healthcare since Obamacare

As of 2015, there were 28,460,300 (10.5% of population) uninsured nonelderly people remaining in the US and of those 24,110,500 were workers (85% of total uninsured) with the remainder (4,349,800) being non-workers (see here for statistics; note that “nonelderly” means under 65 years old and is a commonly used filter as people older than 65 years are eligible for Medicare and, if they are low-income, Medicaid). Clearly, this is a demonstrable overall improvement both in the rate of uninsured compared to the ~16.5% seen steadily prior to 2014 (ignoring the spike in 2009/2010 due to the economic downturn) and in the absolute decline in total uninsured from 45.7 million to 28.5 million (38% decline). It is less clear that the uninsured worker has been helped proportionally when comparing the 26.8 million uninsured workers in 2007 to the 24.5 million in 2015, an 8.6% decline.

I haven’t identified exactly comparable current statistics for the working uninsured by firm size but it should not be a stretch to assume that more than half of the 24,110,500 working uninsured fall into the category of small business owners and their employees (recall it was 63% in 2007). Following the same percentages as found in 2007 and adding their dependents would infer that 70% of the total population of the current uninsured can be attributed to small business (<100 employees) owners, their employees and their dependents. Other articles show that the uninsured rate among mini-business (<50 employees) workers has declined from a 27.4% rate (13.9 million) in 2013 to a 19.6% rate (9.8 million). Adding in an adjustment for their dependents, this leads to about 45% of the total uninsured population is attributed to mini-business owners, their employees and their dependents. One reason for this high percentage coming from mini-businesses is that there is not a healthcare mandate for businesses of this size. The threat of Obamacare penalties led to 97% of small businesses with more than 50 employees offering coverage in 2016 while only 53% of small businesses with less than 50 employees chose to do so [see here].

On the cost side, we find that from 2008 to 2016, family health insurance premiums for small firm (3 to 199) employees increased 38% while worker contributions increased 61% over this same period. Contrast this with family health insurance premiums for larger firms (>200 employees) that increased 42% with worker contributions increasing 58% during the same period. Clearly, we can see that small business premiums increased less than large firm premiums but the worker contributions from small firms outpaced those paid by larger firms as small firms were forced to pass increases in premiums on to their employees. Put simply, small firm employees saw their out-of-pocket premium cost for family coverage increase by 61% during this period. [See here for above statistics]

A recent statement to the US House of Representatives Small Business Committee proclaims numerous benefits to small businesses due to Obamacare. Some of the structural benefits described are valid from my perspective: small business employees are pooled across the entire state market and not based upon a single firm and minimum participation rates can be avoided when enrolling during a special enrollment period (more on this later). However, it’s difficult to separate the impact on mini-businesses due to supportive small business policy from that due to the individual mandate and the expansion of Medicaid. Figures from mid 2016 indicate that the state and Federal Marketplaces have enrolled some 11 million participants while an additional 15 million people have enrolled in Medicaid since eligibility expanded (a 27% increase). At the same time, there are 14.4 million uninsured adults who are eligible for Medicaid but not enrolled. Of this group, 57% are full or part time workers who, together with their dependents, account for 72% of those uninsured adults eligible for Medicaid but not enrolled. Of the 8.2 million working, nonelderly adults who are eligible for Medicaid but not enrolled, 59% (4.8 million) work for small firms with less than 100 employees.

Further complicating the understanding of the real benefits to small businesses is the fact that all the current data is based on costs for 2015 and 2016 plan years. None of the analyses and conclusions incorporate the severe increases in Obamacare policies that have been seen for 2017 and the reactions of small business owners and their employees. As an example, I will describe my own experience and that of employees in the small businesses that I work with.

My Personal Experience with Obamacare as an Individual and a Small Business Owner

In a prior post about the competitive importance of small business employee benefits, I described my experience with Obamacare and I will review it here as well. I first participated in Obamacare at the end of 2015. Prior to then, I was enrolled in a company-sponsored plan (Platinum level) from a former employer that I retained via COBRA at full cost (~$1,650 per month). Once the 18-month COBRA period expired, I enrolled in Obamacare via Healthcare.gov and the policy that I purchased for 2016 was a Bronze PPO plan provided by Humana. This plan was far inferior to my prior plan and included high deductibles ($6,450 individual/$12,900 family) and a monthly premium of $882 for my family of five. I don’t think we used or benefited from this policy at all during 2016 as my family is young and healthy for the most part and we certainly didn’t come close to reaching the individual or family deductibles. This Bronze policy seemed like a reasonable option at the time as I was paying $1,650 per month the prior year and not benefiting from that policy much either.

But my situation changed at the end of 2016. In Arizona (where we live), almost every reputable provider dropped out of the Obamacare exchange. Humana, UnitedHealth, and BlueCross BlueShield (BCBS) of Arizona all decided not to offer any plans in the individual Marketplace. For 2017, there is a single plan offering in Bronze, Silver, and Gold variations for my family provided by AmBetter. This particular plan is worse for us than our prior year plan as it is an HMO plan rather than a PPO plan and the hospitals/doctors participating in their HMO didn’t include any of the providers that we prefer to use. The Bronze level version of this plan for 2017 was quoted to us for about $1,870 per month and had higher deductibles ($6,800 individual/$13,600 family) than the Bronze level plan we had in 2016. The quoted monthly premium amounted to an increase of 112% in addition to the higher deductibles. That meant that our monthly premium for a Bronze level plan in 2017 would more than double to buy worse insurance as compared to our 2016 Bronze level plan and would be even more expensive than the Platinum level plan that we had in 2015.

Some of the employees for companies I work with had the same experience and while they were not highly paid employees, they still were not eligible for government subsidies to mitigate their increased costs. This was a bit of a mystery to me as most of the comments that I heard from news coverage indicated that almost everyone experiencing increased premiums for 2017 wouldn’t actually pay more out of pocket due to the availability of government subsidies. Looking further, what I found was that subsidies come in two forms: a) expanded Medicaid eligibility; and b) Premium Tax Credit Subsidy Caps. The expanded Medicaid and associated Children’s Health Insurance Program varies by state but basically provides medical insurance for most people whose income is less than 133% of the Federal Poverty Line (“FPL”). The Premium Tax Credit Subsidy Caps provide limits to how much an individual must pay for a health insurance plan as a function of their income and the FPL with all subsidies ending at 400% of the FPL (see IRS Bulletin). Here’s a table to visualize the limits using 2016 numbers:

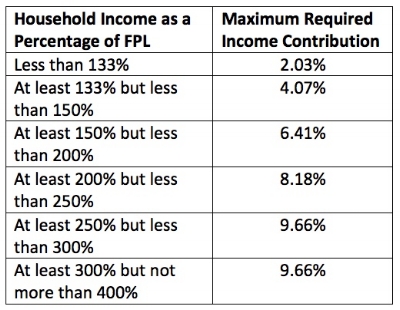

I was confused when I saw this as the employees that I was working with to understand why they weren’t eligible for subsidies fell within the range of the Premium Tax Credit Subsidy. Looking a bit more deeply, the Premium Tax Credit Subsidies are on a sliding scale and diminish the closer you get to the 400% FPL limit. The IRS posted the following table for 2016 to explain the sliding scale:

To take an example, a single mother with one child earning $55,000 per year (343% of the FPL for a family of two) is not eligible for expanded Medicaid assistance as the income limit in her case is $21,307. According to the above table, she would be eligible for Premium Tax Credit Subsidies that impose a healthcare policy cost limit of 9.66% of her income. That means that her cap for health insurance premiums is $5,313 per year or $442.75 per month. This limit was already a large increase for her but somehow, she was not eligible for subsidies after submitting her application. Several other employees had the same experience of dramatically increasing premiums but being turned down for subsidies. I’ll admit that the whole exercise left me confused.

In search of a better answer for all of us, I began exploring healthcare insurance options for small businesses. This search lead me to the Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP) for businesses with 50 or fewer employees that is part of Obamacare and parallel to the individual marketplace. I was surprised by what I found. As it turns out, insurance companies are required to combine participants from small businesses together statewide to create a more balanced risk pool. In fact, BCBS of Arizona decided to participate in the SHOP marketplace even while they pulled out of the individual marketplace. They offer a Bronze PPO plan for 2017 that’s better than the Humana plan that I had in 2016. Better means it has the same network of hospitals/providers that we prefer and the deductibles are lower ($6,000 individual/$12,000 family). Further, the cost of the BCBS Bronze plan for my family via the SHOP marketplace is only $1,307 per month. This represents a 30% cost reduction versus the inferior insurance offered through the individual marketplace. Further, the cost of the premiums paid through the SHOP marketplace are deducted from employee pay on a pre-tax basis, whereas premiums paid through the individual marketplace are after-tax. While the SHOP option created a great cost avoidance, let's not forget that it's still a painful 48% increase from our comparable insurance cost in 2016. The only constraint for implementing the SHOP insurance plan was that at least one employee not related to the business owner must sign up.

In addition to getting better insurance for 30% less cost, there were two other important policy benefits of SHOP. First, if the company enrolls between November 15th and December 15th then there is no participation rate requirement. That’s very important for small businesses. If you don’t enroll your business during that window, then most states require that at least 70% of the eligible employees accept the invitation to join the company-sponsored health insurance offer. This is a huge hurdle for most small businesses to overcome when attempting to initiate a new plan as many of the people who have chosen to work for a small business that does not offer a health insurance plan upfront have alternative insurance (such as coverage from a spouse’s plan) or they simply do not want to pay for it. The company in this example had tried and failed to implement plans in the past or had their plans canceled by the insurance company due to low employee participation. For 2017, we were able to achieve only a 25% participation rate even with our determined effort to make sure every single employee created a healthcare.gov account and formally accepted or declined the offer for coverage. Allow me to reinforce, the small business enrollment period that removes the participation rate requirement for a group plan is very important for small businesses who want to initiate a new plan.

The second important policy benefit of SHOP is that the employer has complete flexibility regarding the amount of the employee premium to pay. The employer can pay as little as 0% of the employee premiums or as much as 100%. There are incremental tax benefits to consider if the employer contributes at least 50% of the employee premiums but this is structured as a sweetener not a penalty. In prior efforts to implement coverage, there was generally a minimum contribution level for the employer. This is a big barrier for small businesses to initiate a new group plan for their employees. Small businesses need the ability to ramp up the cost of providing a group plan over time rather than attempting to climb a high financial cliff at the outset.

My key learning from this process was that small businesses with less than 50 employees can implement a SHOP plan at no cost and allow their employees to benefit from having a better and substantially less expensive health insurance option versus the individual marketplace. The key to this ability, however, is retaining the above two key policy benefits currently found in SHOP.

Concluding Thoughts

Personally, I don’t have a real preference as to whether Obamacare is repealed and replaced or if we choose to work on improving it. I think either approach can lead to a better system that corrects some of the difficulties that I’ve described. But, based on my experience in Arizona, significant changes need to happen quickly to bring insurance companies back into the individual marketplace and to drive down the monthly premiums. From a small business perspective, while there was again only one insurance provider participating in SHOP for Arizona, the provider was reputable and well-established and the cost was 30% less than the comparable offering on the individual marketplace. The SHOP component of Obamacare thus seems to be working better than the individual marketplace.

No matter the direction, the biggest issue that I see for small businesses based on my own experience is finding a way to maintain these three policies:

Small businesses have a defined enrollment period during which the participation rate requirement is not enforceable.

Small businesses have complete flexibility regarding the amount of the employee premium to contribute.

Small business employees are pooled across the entire state market so that premiums are not based upon a single firm but rather on the entire state-wide pool of small business employees.

If these three policies can be maintained whether we pursue repeal and replace or improvement, then small businesses will be able to support employees by adding new group health insurance plans while gradually increasing their employer contributions as business performance allows.